From: Snook (The Elder) at Home

Wherein Snook distinguishes between Theatrics and the Theatre.

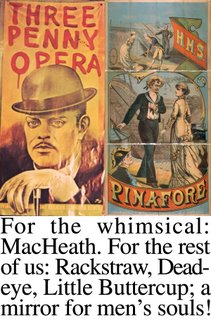

Wherein Snook distinguishes between Theatrics and the Theatre.I took in a preview performance of The Threepenny Opera last week, and must admit to having been left a bit cold by it.

The production itself didn't want for too much; it wasn't stellar, but it did contain some impressive individual performances. And even the ones that weren't so impressive managed anyway ... Against considerable odds in some cases. (Take my treatment of Albert Schultz. I don't know what it is specifically about this fellow--I have no particular quarrel with him either as an actor or as a man--but I simply can't help the feeling every time I see him that he's a fat, smug, son-of-a-bitch. That being so, and the unfortunate coincidence of his playing the lead role also being so, I spent a large part of the performance craning my head over the railings of my balcony seat and hissing "Schultz! You're a hack!" every time he came within earshot of me ... Never fazed him.) And the instrumental accompaniment to the action seemed more than fine, though I'm no judge of such things.

In the end, I can't help thinking that the reasons for my disenchantment lie with the libretto--or, that is to say, with the librettist; with Bertolt Brecht himself ... The man was just too impressed with human squalor. Which I don't entirely begrudge him. Such stuff, after all, can be very grand and compelling, and is almost as likely as pornography or gun play to put bums on seats. But as theatre--as art that is--filth, hunger, the impulse in men to do harm to their fellow man, all these presented as the sine qua non of human existence strikes me as a little bit--well--weak, what? Lacking a bit in the old imagination department.

I mean, the thing about human squalor--which, of course, does exist, and is really dreadful and all that--is that any preponderant focus upon it draws us away from the rea

l meat of mankind's frailty: his absurdity. (Indeed, even to call it absurdity gives it a weight of importance that risks undermining any true (that is, artistic) depiction thereof. Let's call it, instead, his ridiculousness. Nay, even, his buffoonery!)

l meat of mankind's frailty: his absurdity. (Indeed, even to call it absurdity gives it a weight of importance that risks undermining any true (that is, artistic) depiction thereof. Let's call it, instead, his ridiculousness. Nay, even, his buffoonery!)And in respect of this, it seems to me that that redoubtable old sausage-grinder to the world of musical theatre, Sir W.S. Gilbert, was the greater artist by far; and that in something like H.M.S. Pinafore we are provided with a more truthful account of the mutabilities of existence, the upsets of fortune and rank, and the complexities of les affaires de coeur that have dogged mankind's steps ever since his introduction upon that other--that is: this--terrestrial stage.

Indeed, by all accounts, we might well and truly observe of Herr Brecht, Dramaturgical Innovator, fair Josephine's appraisal of Sir Joseph Porter: that "he is a truly great and good man, for he told me so himself, but to me he seems tedious, fretful, and dictatorial."

<< Home